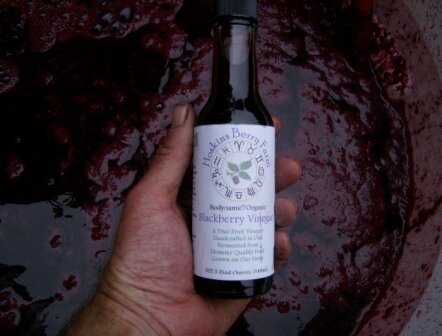

A Holistic Approach: This Oregon farmer is crafting all-natural blackberry vinegar

By Nicole Newman // Photos courtesy of Hoskins Berry Farm

“Food and drink have been industrialized to the point that people don’t even value it anymore. As people wake up to good food and drink and flavors and colors and aromas... that’s just a really healthy thing for humanity. ”

Using organic and biodynamic practices, Jim Fullmer of Hoskins Berry Farm in Oregon is producing blackberry vinegar with a mother he’s been nurturing since the ‘80s. “We’re a tiny farm,” Fullmer says. “It’s 30 acres. We don’t want to grow into bigger acres to hit a certain supply demand. We’re trying to keep it going with what we’ve got. And that’s an interesting challenge because the broader marketplace pushes you to grow in size and volume, and we don’t want to.” Writer Nicole Newman had the chance to ask Fullmer about his biodynamic farming, how he makes his naturally fermented vinegar and what the future holds for Hoskins Berry Farm.

Nicole Newman: What were you doing before you started Hoskins Berry Farm?

Jim Fullmer: I was in Montana. I was an apprentice on farms on the Western side in a little town called Victor at a farm called Lifeline Farm. We were starting a dairy herd and I had never been around dairy cows before. We brought in a herd of wild Holstein cows that were living on the range in eastern Montana. That’s where I was prior to Hoskins Berry Farm. I was in and out of Oregon in that time, too.

NN: What made you decide to launch the farm? How did you hone your craft?

JF: This particular farm was an opportunity in about ‘86 or ‘87. In the northwest of Oregon, it was bad economic times and the land was cheap … we’ve always had berries. We had strawberries and raspberries so we wanted to keep that going. I was the early days of organic farming and it was a good time for farmers. Originally we were growing for companies like Cascade Farms when they were a startup. They got passed through multiple entities like Disney and General Mills and because of that, as these companies got bigger, the prices for things went down.

Long story short, the idea popped into my head, “what if we made this into a vinegar?” I read up on vinegar making and it’s actually a very simple process. Ultimately, any piece of fruit that drops to the ground ends up a vinegar. We took five or 10 pounds out of a bucket, smushed it and fermented it. It ferments on its own yeast and creates its own [blackberry] wine. That was the start of our mother; about 20 to 25 years ago. And if you nature her, she’ll just keep going forever. It’s still the mother that we add to our vinegar.

The way I learned about wine was working with biodynamic wine producers. I was the director of the Demeter Association. The Demeter doesn’t allow for manipulations. In making a wine, it won’t let you add yeast. You need to cultivate those yeasts on the skin of fruit. So, that’s what we did. And the process of making vinegar is that step from alcohol to acid and that’s what mother of vinegar is. It’s vinegar that hasn’t been pasteurized.

NN: You approach farming with a holistic view of nature. Can you tell me what that means to you?

JF: That concept is this nature that is unified. If you look at a farm as a self-regulating system — Rudolf Steiner used the term “organism” — it has all these parts and when you look at the natural world that way, that’s how it operates. It’s like an undisturbed forest. It’s regenerative and doesn’t require additives from the outside. And a holistic view of nature goes beyond the fence line of the farm.

NN: Why do you choose to use biodynamic farming practices?

JF: It wasn’t really a choice. It was more organic than that. It just unfolded. Farming by nature. This is one occupation where if you’re the one doing the farming, it throws you out into the elements and you’re having to deal with the macrocosms all the time. The seasons, the weather, the length of the day. It all effects your life. Farmers tend to look at those wider connections and they totally dictate what you do on any given day. It’s intended to heal things, the Earth in particular.

NN: How is your blackberry vinegar made?

JF: It’s beautifully simple. The fruit is growing on the field. Come late August, it starts ripening. It’s abundant. We pick it and go through any given patch of berries four or five times during a month. Usually what stops it is the change in the seasons. When fall comes, the rain starts and the quality of fruit goes down. We harvest it, we freeze it to break down the cell walls so the fruit essentially becomes a liquid, and then we thaw it. Then, all those native yeasts that live on the fruit start going to town. The yeast eat the sugar and it starts fermenting. That turns into alcohol. It’s not like a wine alcohol, it’s a lower alcohol percentage. It goes through the process where it starts bubbling and foaming. You’re plunging it like you would a red wine. It literally liquifies and turns to wine. After about three weeks, it fully ferments to wine and at that stage, we add the mother of vinegar from past batches at a ratio of about one quarter vinegar to three quarters wine. This happens in an oak barrel. That’s it. We don’t have to intervene much at all. It’s pretty amazing how uniform it is from year to year. There’s the concept of terrior and it’s a sense of place in the flavors and aromas. The same things happens with vinegar.

NN: Why is it so special?

JF: It’s a real fruit vinegar. It’s literally a fruit transformed to vinegar. A lot of times you’ll have a blackberry or cherry vinegar that’s really just a grape vinegar with flavoring added. But this is literally the fruit. And then the flavor is unique because of that. This vinegar is intense. It stays on the palate for a long time, and then goes up into your ears and your eyes. It’s not for everyone! It’s got this beautiful color that the berries create. But it’s not a balsamic. We’re looking at playing around with that but that’s not what we have right now. People use it for salad dressings, as a marinade for fish or chicken. Some people use it medicinally. I don’t fully understand the medicinal value but apparently it’s effective with blood sugar. They literally take a tablespoon of it. Food is medicine, too.

There’s this point in a project like this where the goal is to only make vinegar with the fruit grown on this farm. There’s been pressure and interest from labels that want us to buy in fruit. We really don’t want to do that. It opens up this interesting challenge because there’s a limited supply. It’s only five acres of fruit, maximum. So when demand gets bigger than supply it’s just gone. And when it’s gone, it’s gone until the next year.

NN: Tell me about the many herbs you grow.

JF: In addition to berries, we also grow medicinal herbs like colangela, red clover blossoms, hemp. They literally rotate between the berry acreage between the rows and it’s part of the regenerative nature of the farm.

NN: You harvest mainly during August. What does the rest of the year look like for you?

JF: Out here, spring, summer and part of fall is the growing time. When winter happens, it’s not like things stop. It’s just a different mood. Things go dormant, but out here it stays green. It’s a temperate rain forest. There’s projects that go on related to cows. We’re making sure the Earth is covered with greenery like cover crops. It’s really wet. Things definitely slow down, and like a lot of farmers, I’ve always had off-farm work to make ends meet. For a long time, I was the executive director of the Demeter association. Now I have multiple consulting projects around the U.S. One in Oklahoma is with a baby food company connected to Jennifer Garner, the actress! And then there’s one down in California as well. I travel a fair amount, more so in the winter than the summer.

NN: Why is the maker movement so important to you?

JF: It’s always been really important to me. I first started to get a taste of the idea through the Good Food Awards. This was maybe 2013 or 2014, and somehow our vinegar found its way there. It won the gold seal, this that and the other thing. My first exposure to all these artisan food producers. They’re all small, quality-focused, serious about their craft. Just tasting all of that stuff got me interested in the idea of what tasteMAKERS is doing now. Food and drink have been industrialized to the point that people don’t even value it anymore. As people wake up to good food and drink and flavors and colors and aromas… that’s just a really, healthy thing for humanity.